Part I

Part I

In the summer of 1970, I landed my “dream” job just by being in the right place at the right time, with a recommendation from the right friend. How else could an untrained young black man back then get hired as a journalist by Newsday, a major suburban New York newspaper? I’ll explain.

The right place turned out to be Ft. Bliss Army base in El Paso, Texas; the right time materialized for many black achievers after the 1968 Kerner Commission, appointed by President Lyndon Johnson following more than 150 riots in major U.S. cities between 1967-1968, determined that people of color were woefully under represented and under employed by U.S. corporations and media organizations and that they should be provided access to mainstream America’s better paying jobs. I met the right friend, Les Payne, in 1964 when we were Second Lieutenants in the U.S. Army stationed at Ft. Bliss.

To be clear, my access to the world of journalism did not come about because white America voluntarily opened its doors due to a change of heart about racial discrimination. Black folks slowly but surely blew those doors down. Rosa Parks pushed them opened a wee bit in 1955 by refusing to give up her seat on a segregated Alabama bus. Eight years later in 1963, Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, delivered during the March on Washington, left them ajar. The rioting that followed in 1967 stirred President Johnson to act and to appoint the Kerner Commission.

The report’s damning assessment that the nation was becoming “two societies, one black, one white” created by white institutions, also blamed the media, noting, “The press has too long basked in a white world looking out of it, if at all, with white men’s eyes and white perspective.” In the aftermath of the Kerner Report, many U.S. corporations and media organizations added people of color to their staffs. Les was hired by Newsday in 1969; I followed a year later.

Before we became journalists, we both began military careers as Army officers in 1964 in Ft. Bliss, sharing the same bachelor officers’ suite. Les became a Second Lieutenant, after graduating from the University of Connecticut (English major) and completing its Reserve Officers Training Corps (ROTC) program. I also received my gold bars through ROTC an earned a BA degree in mathematics from Hampton University in Hampton, Virginia. Les arrived at Ft. Bliss months ahead of me but had lived alone because several white officers refused to share a suite with him. “Am I glad to see you,” Les greeted me in that gravelly baritone voice that might have been intimidating had it not been accompanied with a warm smile.

As we talked, I quickly concluded that my roommate functioned intellectually and intuitively at a level beyond anyone I’d ever met, without any hint of pretentiousness. Les spoke deliberately, with ease and chose his words carefully. When responding to a question, he gave lecture-like clarifications, when necessary. If he disagreed sharply with my views in sports, politics or race, he replied only with his piercing dark eyes and a grin that morphed into another smile. He enjoyed imitating the great leaders of that era, Martin Luther King, John F. Kennedy, Malcolm X, etc., and often gave near flawless renditions of their public statements.

Ft. Bliss was then the home of the Air Defense Artillery training school, which, among other things, conducted a nine-week training program for junior officers destined to serve at Nike Hercules missile sites in the U.S. and abroad. Though my first Army training stint was short, it proved to be long enough for Les and me to begin a friendship that lasted more than 50 years. After Ft. Bliss, I made a few other brief stops before settling in at Ft. Wainwright in Fairbanks, Alaska.

Les and I had accepted Regular Army (RA) commissions, which carry a three-year commitment but guaranteed the officer’s choice of first-duty assignment. RA officers were required to complete the nine-week Ranger School training or the three- week Paratrooper School, both based at Ft. Benning, Ga. Les became a Ranger; I became a paratrooper. A Reserve Officer’s commission carries a two-year commitment. I assumed that I could resign my commission after three years and go home. A few months before completing three years, I submitted my letter of resignation to the Pentagon.

About a week later, I received a phone call from a field grade officer at the Pentagon, who said, “Son, you’re RA, serving at the pleasure of the President. You can pack your bags, but you’re not getting out. You’re going to Vietnam!”

“But I don’t have orders for Vietnam,” I retorted sharply.

“Yes, you do, they’re on the way. You’ve been extended 18 months,” he said.

Same thing happened to Les, who began his Vietnam tour a year ahead of me. He spent a year in Saigon as General William Westmoreland’s information officer. The staff Les supervised included Bill Nack, an enlisted soldier, who joined Newsday as a reporter after his Army discharge. Les’ duties included writing Westmoreland’s speeches, acting as guide to new members of the mainstream media upon their arrival in-country and editing and publishing the Army’s newspaper. When Les completed his Vietnam tour, he was shipped back to Ft. Bliss, where his service was extended for an additional 18 months. Same thing happened to me upon my return from Vietnam in 1969.

Four years and several different assignments later, we were reunited at Ft. Bliss as Army captains. We exchanged war stories, our views regarding the ongoing Civil Rights struggle and the welcomed change in our marital status. We both were married with children. My first wife, Shirley, and I had a son; Les and his wife, Violet, had a daughter.

Two Les Payne stories involving race were on the Ft. Bliss black officers’ rumor mill when I returned to the base. They demonstrated Les’ enviable level of character and fearlessness, traits that became his calling card as a journalist. Les told me about the first story; a black junior officer, who was a mutual friend, told me about the other.

While serving as a battery commander of an Air Defense Artillery company, a black soldier under Les’ command was to face either Article 15 or court martial charges. After conducting his own investigation, Les concluded the solider was innocent and should not be prosecuted. Les’ boss, a white battalion commander, disagreed and ordered Les to charge the soldier anyway. When Les refused, he was fired and ordered to clean out his desk and prepare for reassignment. Before Les had finished emptying out his desk, his commander, without explanation, rescinded the order and reinstated Les as battery commander.

In the second story told to me by a black officer, Les drove into El Paso on an off day dressed in civilian clothes to attend a White Citizens Council meeting. No kidding. His input prompted some discussion but didn’t change any minds about the racial issues of that era. He left the meeting without incident.

During the early months of our reunion, I contributed stories to ‘Uptight,’ an urban-oriented magazine that Les had formed. The magazine included profiles and features that focused on black newsmakers, politicians, entertainers and other celebrities. Six months later, Les left the Army to join Newsday as a reporter. Nack, who became Newsday’s renowned horse racing reporter and author of Secretariat: The Making of a Champion, had recommended Les for the job. Months before I left the Army with plans to pursue an MBA at Atlanta University, Les urged Newsday editors to hire me. After a two week tryout, they did.

I assumed that because rookie journalist Payne had executed his reporting and writing skills with the efficiency of a past master, they trusted his judgement. There’s no doubt that Les’ recommendation helped me, as much as Nack’s backing helped Les. In September 1970, I became the eighth black (seven journalists, one photographer) to join the conservative-leaning Long Island tabloid.

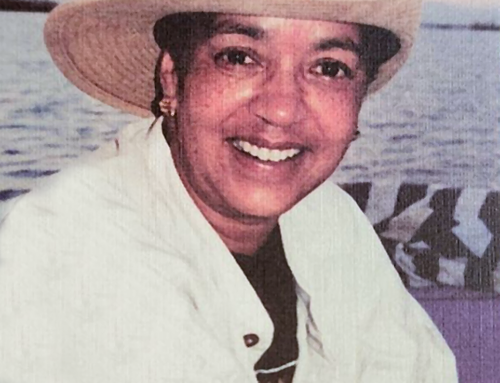

Les died of a heart attack on March 19, 2018. He was an extraordinary journalist, remarkable communicator and special human being. I’m proud to have been among the first of thousands of young journalists and students who were mentored, taught, supervised, inspired or befriended by Les Payne during his 37-year newspaper career and for our lifetime friendship. His legacy lives on through his work as a journalist and through the hundreds of journalists – black and white – who admired his commitment to confront and, at times, silence or neutralize the divisive voices that continue to stain our nation’s soul.

“I saw myself as a kind of lead pipe in the hands of people who did not otherwise have a weapon to counter such things,” Les once said.

In a tribute to Les, DeWayne Wickham, dean of the School of Journalism and Communication at Morgan State University in Baltimore, Maryland, former syndicated USA Today columnist and one of Les’ longtime colleagues and friends, wrote:” History should not be allowed to forget Les, as it has so many other blacks who championed the race. We owe it to him not only to thank him for his service but also to emulate his determination to be a truthteller in a profession that more than ever before needs a Les Payne.”

Les’ wife, Violet said, “I feel very humbled to have been his wife. I enjoy hearing about all the people that he inspired. He had such great hope for the younger generation to carry on.”

Reflections of my early years as Les’ colleague at Newsday begin tomorrow

Another excellent article Doug. Your first article (Part 1), allowed us to view your introduction to the Pulitzer Prize winner, Les Payne. My first introduction to Mr. Payne was through you Doug, you Earl Caldwell, Jack White, Les Payne and I sat and had lunch not far from Hampton University. Just a couple of sandwiches and soda bottles at our local sandwich shop with People whom I felt at the time were giants in the journalism communities, more specifically of our African communities. Journalist who weren’t afraid to speak the truth and not pussy foot around reality and facts. Les Payne’s broad stature, baritone voice and piercing stare had me hooked on every word he said that day. Thanks for bringing that cherished memory back to me once again.