Part II

Part II

Les Payne proved to be a quick study as Newsday’s beat reporter, covering the town of Babylon, N.Y. He also drew high praise from editors and several fellow reporters for volunteering to tackle riskier assignments during his first year on the job. His most dangerous assignment surfaced in the summer of 1970, when he spent a week undercover, posing as a migrant worker on a farm in Riverhead, NY.

He picked cotton alongside his grandmother on a Tuscaloosa, Al. farm when he was eight-years-old but became aware of the hardships of the migrants’ life years later through Edward R. Murrow’s coverage of the migrant worker for CBS. Les wanted to present a day-by-day depiction of life from the migrant’s perspective. In the Newsday story, he also revealed that the Riverhead migrants’ overseer took advantage of his workers by, among other things, stealing money from their weekly pay. “I pretended to be a deaf mute because I doubted if anyone would have believed that I was a migrant had I opened my mouth,” Les said.

Les’ fellow black reporters were grateful that he never hesitated to open his mouth as their spokesman whenever hints of bias surfaced at Newsday or other media organizations. In less than a year on the job, he organized and led Newsday’s seven-member Black Caucus. The paper’s top editors often struggled to break even when facing Les at the negotiating table.

A striking example of Les’ power of persuasion came to light after fellow Black Caucus member Robert DeLeon informed him of a national meeting of more than 50 black journalists that was set to be held June 28, 1970 at Lincoln University in Jefferson City, Missouri. It was organized specifically to allow the nation’s black journalists to express publicly their support for Earl Caldwell, a New York Times reporter, who refused to testify before a grand jury investigating the Black Panthers. DeLeon suggested that Les ask Newsday editor David Laventhol to send the two of them to represent the newspaper at the black journalists’ meeting, but Les dismissed that idea.

“Why not demand that they send all of us?” he said. After some resistance, Laventhol consented; he sent all seven journalists to Jefferson City.

The New York Times published a story about the meeting, and Caldwell, free pending his appeal of the conviction, attended. Explaining his decision to defy a court order, Caldwell said, “I refused to be an informant for the FBI, and I refused to forsake my pledge as a journalist not to identify my sources or to share any off-the-record information or conversations that I might have had with my sources.”

On Newsday’s decision to send seven reporters, Caldwell said, “I couldn’t believe Newsday agreed to that. Les was truly amazing.”

The attending journalists also formed the National Association of Black Media Workers, a precursor of the National Association of Black Journalists (NABJ), which was founded in 1975. Les, an NABJ co-founder, later became its fourth president.

The first wave of black reporters that were hired by major newspapers in the wake of the Kerner Commission’s report arrived in 1969. Les was grateful for Bill Nack’s recommendation, as was I for Les’ recommendation a year later. We both realized many years later, however, that while those recommendations helped the two of us individually, someone much higher in the Newsday’s command chain had committed to progressive change, not tokenism, in the hiring of people of color.

For a while, I suspected Laventhol, who seemed enthralled by Les’ routine display of competence and intellect, which caused many whites to recoil, not embrace. He often took notes while Les presented the Caucus’ demands or concerns and ranked Les among the most savvy and gifted reporters Newsday had hired during his tenure. Years later, I came to believe, as Les did, that Bill Moyers, a native of Hugo, Oklahoma, was the force behind the rapid influx of black reporters at Newsday. In 1967, Moyers resigned as President Johnson’s White House Press Secretary to become Newsday’s publisher. He had helped write the Democratic party platform of 1964, which had a strong commitment to civil rights, and played a key role in the passage of LBJ’s landmark congressional bills: The Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He was on the scene when The Kerner Report was reviewed by Johnson.

Explaining his decision to leave his prestigious White House job prematurely, Moyers said the issues he really cared about “poverty, the Great Society, civil rights, were all being drained away by the Vietnam War. The line that keeps running through my mind is the line I never spoke: ‘I can’t speak for a war that I believe is immoral.’” He left Newsday in May 1970, shortly after owner Harry Guggenheim sold his majority share to the then conservative Times Mirror Company.

Four months later, I began my journalism career at Newsday as a beat reporter covering the town of Brookhaven. The Smiths moved in with the Paynes in early September and stayed at least a month, maybe longer. We never felt unwelcomed in their Huntington, N.Y., home and I felt blessed to have Les nearby to keep me from making any embarrassing rookie mistakes. I made some anyway.

Before going house-hunting, Les warned us that the real estate agents would show us homes only in predominantly black neighborhoods — and they did! We managed to buy a home a block or two away from the Paynes by negotiating directly with the owner.

After a year of chasing after the Brookhaven town supervisor and council members and attending civic and political meetings, I decided that wasn’t the job I really wanted. So, I applied for a position in the sports department. When I told Les, he replied with a quizzical look, followed by a grin that morphed into a cynical smile that I’d seen only once or twice before. “You want to work in the toy department? You shittin’ me?” he asked. “I guess I’m still a kid,” I said.

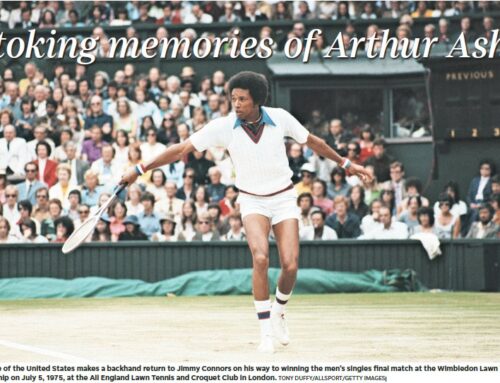

I began my sports journalism career, covering high school sports, football, basketball, soccer. I chronicled Mitch Kupchak, the former Los Angeles Lakers player and later general manager, when he was a Brentwood High School standout. A year later, I moved up a bit and became beat reporter covering the New York Nets of the American Basketball Association (ABA). I also volunteered to cover the 1972 U.S. Open tennis championships, mainly because Arthur Ashe, a friend since high school, was among the favorites. The topic of my first sports column was an analysis of why Ashe was beaten by Ilie Nastase in the U.S. Open final. I saved a copy for Les, who at the time was then on assignment in Europe.

A week or two later, I received a postcard from Les sent from Germany. Turns out, I didn’t have to save the Ashe column after all. The card read: “Doug, I missed the Olympics, but ran smack into the Munich Oktober Fest – not bad for a washed-up quarter miler. Your Ashe view-piece was good, has a sing and soundness about it. I hear football has started and the World Series is on deck. Somehow, I don’t miss either. As for my “humble personality,” F— Humility and seize the time. — les”

The success of Les’ probing migrant-type stories earned him a spot on the newspaper’s elite investigative team, led by Bob Greene. He chose Les and fellow reporter Knut Royce to join him on a more than yearlong investigation dubbed “The Heroin Trail.” The 33-part series, and 1974 Pulitzer Prize winner, traced the flow of heroin from the poppy fields of Turkey to the arms of drug addicts on the streets of New York City. The series later was released as a book.

Les was always seeking stories tinged with danger. That was his nature. “If a story didn’t have an element of danger, it didn’t interest me,” he said. “Reporting is getting information that people in power don’t want you to have.”

In June 1976, hundreds of black high school students were killed in Soweto, South Africa, while protesting the government’s apartheid system. I suspect Les heard voices from the Soweto uprising calling his name. He knew the South African government wouldn’t welcome an American black journalist with open arms. He knew, too, that “the kid” in the toy department knew someone who knew someone that might find a way to get him in. I did.

Part III tomorrow

Insightful “homage” paid to a worthy possessor of huge “gonads-of-courage” — appropriate wrappings for your friend and mentor (read I & II; awaiting III). Glad to see you “back-in-action”.