A note from Doug Smith: Rufus M. Gant was 87 when he died last week in Hampton, Va. after a long illness. He was an outstanding all-around athlete at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and later became one of the top high school tennis coaches in the Tidewater area. His teams won 10 State Black Championships. I was a member of Gant’s teams from 1957-60. I offered these reflections at his funeral June 17, 2011.

A note from Doug Smith: Rufus M. Gant was 87 when he died last week in Hampton, Va. after a long illness. He was an outstanding all-around athlete at Hampton Institute (now Hampton University) and later became one of the top high school tennis coaches in the Tidewater area. His teams won 10 State Black Championships. I was a member of Gant’s teams from 1957-60. I offered these reflections at his funeral June 17, 2011.

When I was a Phenix High School student back in the late 50s, my friends called me Diddy Wit. Even Mr. Gant used to call me that, especially when I did something I shouldn’t have done.   He was like my daddy in that way and he was a father figure to me in so many other ways, as well. To be honest, I doubt very seriously if I would have travelled the road I took if Mr. Gant hadn’t been there to guide me.

Let me explain my journey and the impact Mr. Gant had in shaping it.

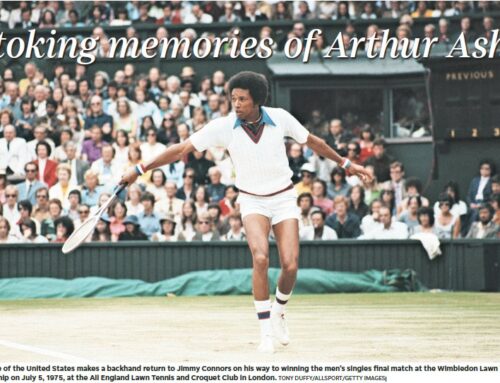

I spent most of my adult life working as a sports journalist for three major newspapers – Long Island’s Newsday, the New York Post and USA Today. Before retiring in 2001, I ‘labored’15 consecutive years writing about the sport I love – tennis. I interviewed and wrote stories about the game’s top players at the high school, college and pro levels and travelled the country – indeed the world – covering major tennis events, including the Australian Open in Melbourne, the French Open in Paris, Wimbledon, near London and to New York for the U.S. Open.

Along the way, I also wrote a couple of tennis books – one on former tennis pro Zina Garrison and the other was the life story of Hall of Fame inductee Dr. R. Walter Johnson, the man most responsible for launching the careers of tennis greats Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe, our first African American tennis champions.

I bring this to your attention not to toot my own horn, but only because in my heart I know that none of it would have occurred if Mr. Gant hadn‘t persuaded me to play tennis. More precisely, he dragged me onto a tennis court when I was 15, put a racket in my hand and worked with me until I was good enough to be a member of Phenix High’s high-powered, varsity tennis team. This he did when I was a sophomore, even though he knew I really wanted to play baseball. He was pushy that way, and, of course, I’m so glad he was.

But what he pushed me to do two years later as a senior, was equally, perhaps even more important. I didn’t receive the scholarship money I needed to attend the college of my choice, Notre Dame. A few days before graduation day, I went to Mr. Gant’s office and told him that since I couldn’t afford Notre Dame, I wasn’t going to college. I was going to join the Army. He asked me to take a walk with him.

We walked in silence to Hampton University’s old gymnasium, which was only a block away from Phenix High.  We sat in the athletic director’s office and waited for Dr. Herman Neilson. When Dr. Neilson arrived, Mr. Gant, without consulting me, told him that I had decided to attend Hampton and play tennis for the Pirates. Dr. Neilson shook my hand and congratulated me on my choice. Yep, once again Mr. Gant pushed me in the right direction, and again I’m so grateful that he did.

In later years, the teacher-student relationship we had evolved into a friendship. However, my respect for him never would allow me to call him Rufus. Just as he had taught me to play tennis, he also gave me golf lessons when I got the golf bug about 20 years ago.  But I can’t say that his input was as effective on the tee box as it was on the tennis court. Twenty years later, I still don’t know where golf ball is going after I hit it on. But I love him still for the effort.

I grew up in the era of racial segregation and like most young black men, I realize now how much I needed someone like Mr. Gant to lean on and how different my life might have been had he not been there. He was one of many unsung heroes of the pre-Civil Rights era who taught young blacks throughout the South to tread confidently, but carefully through their sometimes unfriendly, sometimes hostile environment.

In my book, Whirlwind, I wrote this about Mr. Gant: “He encouraged us to push ourselves beyond the limits imposed by racist policies and frequently urged us to be twice as good as our white competitors.  Mr. Gant also added this warning: “Rejection might come even when you prove yourself, but never stop trying.â€

After integration came to Hampton, Mr. Gant was appointed principal of racially-mixed Hampton High School and there’s no doubt in my mind that he provided the same level of common-sense, do-the-right-thing guidance to his all students there as he did with students of my generation.

It seems to me that his life’s goal simply was to strive to do what he always encouraged me and others to do: Excel, excel, excel and never forget to reach back and help others do the same. That is why he’ll live forever in my heart and – no doubt – in the hearts of so many others who profited from the days he spent on this earth helping young people meet the challenges of adult life.

Leave A Comment