Fans attending both sessions of the Sony Ericsson Open in Key Biscayne, Fl. Sunday got to see the entire contingent of African American tennis pros competing at the elite level. The total number, which was double digits when I first began covering tennis for USA Today in 1986, has dwindled to three: World No. 1 Serena Williams and No. 5 Venus won their third round matches, but No. 13 James Blake was beaten by Tomas Berdych.

For several years now, the sisters and Blake have been the only African Americans ranked in the top 50 in the WTA Tour and ATP Tour computer rankings respectively. That’s worrisome for someone like me who routinely encouraged talented African American juniors to tough it out and pursue pro careers. But judging by the dismissal of three African American leaders during the past two years, United States Tennis Association (USTA) officials apparently have little, if any, concern about the growing absence of African Americans on the tennis courts or in their executive offices.

During Jane Brown Grimes’ two-year regime (2007-08) as USTA president, three prominent African American former pros – Leslie Allen, Zina Garrison and Rodney Harmon – were summarily dismissed from high-profile positions. Allen, a magna cum laude USC graduate, lost her job as U.S. Fed Cup Chair two years ago; Garrison was dismissed as U.S. Fed Cup captain last fall and Harmon was fired as Director of Men’s Tennis last fall. Last summer, Garrison served as the coach of the U.S. Olympic team that competed in Beijing and Harmon coached the U.S. Olympic men’s squad. While all three firings are troublesome, Garrison’s charges of double standards and racism in her lawsuit, which was filed recently, are especially disturbing.

If Garrison proves that the USTA gave her a series of one-year contracts while her counterpart and successor received multi-year deals and that her successor’s salary was greater than that which she received for performing the same duties, the USTA’s current policies are indeed similar to the unfair practices used against African Americans by many major corporations through much of the 1970s and ‘80s. Make no mistake, racial bias continues to be a major problem in these United States.

As a journalist covering tennis since the 1970s, I experienced numerous slights and humiliations because of my color. President Barack Obama spoke eloquently about his own experiences with racism in his books – Dreams from my Father and the Audacity of Hope – and to a large television audience during the Democratic Presidential primaries.

In the tennis world, one of the most frightening examples of racial bias gone amok occurred eight years ago at the Indian Wells event when a crowd of thousands booed and jeered mercilessly the Williams family – spectators Richard and Venus, and Serena, as she competed against Kim Cljisters in the final, for more than two hours. It’s one thing for a crowd to express their displeasure – justified or not – for a few moments, but to continue for nearly two hours as the Indian Wells crowd did, was outrageously excessive. Tournament director Charlie Pasarell said he cringed during the crowd’s unruly behavior but, none of Pasarell’s officials admonished the crowd for its ugly and potentially dangerous exhibition.

“That was the most horrifying experience of my life,†Richard Williams said recently. Neither sister has played at that event since then; the family has vowed never to return despite tour imposed penalties against the sisters for not playing there.

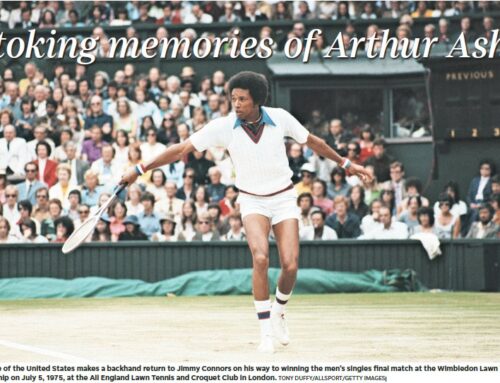

In my view the USTA’s ouster of prominent African American role models might prove to be as damaging to the psyches of young blacks considering tennis as a career. Allen, who rose to No. 17 in the world in 1982 and Garrison, who rose to No. 4 and was a Wimbledon finalist in 1990, have inspired youngsters of every color, but especially African Americans. Allen has a foundation that helps inner-city youths and Garrison for many years ran an tennis academy in her hometown, Houston, Tx. Harmon, who in 1982 became only the second African American male to reach the U.S. Open quarterfinal (Arthur Ashe was the first), was the USTA’s director of tennis for six years and had served the organization ably for nearly 20 years. Two weeks ago, the International Tennis Hall of Fame awarded him its Educational Merit Award.

“It’s an award that Arthur also received, so I was honored,†Harmon said.

Harmon hopes one day to see some of the African American juniors he discovered and trained competing in future U.S. Opens. He hopes, too, that all the work he did as director of the USTA’s Multi-Cultural Development will not be abandoned.

Allen, Garrison and Harmon were the only existing link between Althea Gibson and Ashe, the first African American tennis greats, and the Williams sisters, Blake and future superstars of color. Let us hope that current USTA president Lucy Garvin will look for ways to strengthen that chain, and choose not to continue to shatter it.

Leave A Comment