Twenty-four years ago, the USTA honored the late Arthur Ashe by etching his name on the U.S. Open stadium court, an act that heightened the significance of his contributions, not only to the sport but to the world. Last week, three UCLA historians forged ahead with its Ashe Oral History project, designed to ensure that many others, including each incoming UCLA student body, is aware of Ashe’s story. Slowed by the pandemic, the historians updated the status of the project at a mid-town New York hotel.

“Ashe was an alum that exemplifies so many of UCLA’s values,” said Professor Patricia Turner, director of UCLA’s Arthur Ashe Legacy Project. “It is particularly appropriate and timely to emphasize that he was what we want our students to become.” Turner said The Legacy Project also supports an Ashe scholarship/intern program, an Ashe Virtual booth (South Plaza) at the U.S. Open, and the Oral History project, which is headed by Yolanda Hester, with assistance provided by Chinyere Nwonge. “Many people will know him as a tennis player, but his impact was much broader,” said Hester. “Throughout his life, he fought for the rights of oppressed people and devoted himself to social justice, health and humanitarian causes.

Ashe left UCLA in 1966 with the 1965 NCAA singles championship, a degree in business administration and a fervent desire to excel on whatever career path he chose to travel. In his book Days of Grace, Ashe wrote, “I was adamant about not giving myself exclusively to making money. If God didn’t put me on earth mainly to stroke tennis balls, he certainly hadn’t put me here to be greedy. I wanted to make a difference, however small, in the world, and I wanted to do so in a useful and honorable way.”

The record shows that the Hall of Fame tennis pro, businessman, international civil rights activist and humanitarian did it his way with an abundance of success. Ashe’s achievements in the rich man’s sport were even more extraordinary for a black man of poor beginnings who grew up in Richmond, Va. during the era of racial segregation. Though he was a better player than most of Virginia’s top white juniors, he was forbidden by law to compete against them on the state’s public courts. When Ashe turned 14, the black tennis community sensed that he was our Jackie Robinson, destined to dispel the notion that talented black juniors couldn’t compete successfully against top-ranked white juniors.

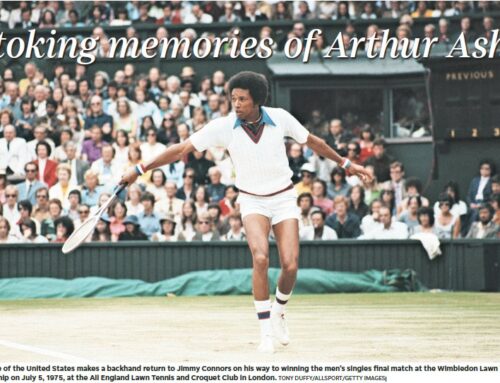

Everywhere he played, everywhere he went, blacks opened their homes, their refrigerators, their pocketbooks and their hearts to help him accomplish our mission. He accepted his role as a black sports pioneer with little resistance, giving up, among other things, a chunk of his childhood. Years later, he won 33 pro events and continues to be the only U.S. black male to win the U.S. Open (1968), Australian Open (1970) or Wimbledon (1975), all major titles. He was a superstar without flair or arrogance; Arthur could only be Arthur.

In a Washington Post remembrance of his close friend and client published 10 years after Ashe died of AIDS in 1993, attorney Donald Dell wrote, “As he matured, Arthur developed into a genuinely intellectual man: inquisitive, studious, in love with learning. And from his learning came the desire to champion many causes, something that he did rationally and reasonably.

“On the subject of race, I was surprised when I read a quotation from Arthur to the effect that the toughest obstacle he had ever faced was not his two open-heart surgeries or even AIDS but, rather, ‘being born black in America.’ We had a long discussion about that. He felt I didn’t understand. He told me that regardless of prominence, every black person in this country was made aware every day that he or she was black. He had faced racism as a young man growing up in Richmond, and regardless of his success, he continued to have to deal with it his whole life.”

Ashe and Dell began their client/attorney relationship in 1970 and renewed it annually for the next 22 years, with a handshake. “I was always struck, in my personal relations with Arthur, by his overriding sense of trust,” Dell said. “Arthur strongly believed, despite all he had seen and been through, that there was a lot more good in people than bad.”

Endorsing the project in the introduction of a UCLA publication, Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe said, “UCLA has not only stewarded Arthur’s legacy but has found innovative ways to take it to the next level and showcase its continued relevance. I take pride in how these efforts have magnified and look forward to seeing how they will continue to grow in the years to come.”

Leave A Comment