Tennis fans on both coasts spent time last Saturday remembering their roots in ceremonies recognizing Jack Kramer, a man who helped shape the pro tours, and Baltimore’s Druid Hill Park, a place where the American Tennis Association (ATA), an organization that changed the face of tennis in these United States, was formed.

In Los Angeles, several hundred people gathered at UCLA’s Tennis Center to pay tribute to Kramer, who died two weeks ago. Kramer, who was 88, won the U.S. Open in 1946-47 and Wimbledon in 1947 and soon afterwards formed the first pro tour. Later, he became a prime mover in developing the existing men’s ATP Tour. Tennis historian and ESPN analyst Bud Collins has called Kramer, “the most important man in the history of tennis.” Former pro and commentator Barry MacKay said Kramer was “the best promoter the game of tennis ever has had and ever will have.” Former pro and fellow promoter Charlie Pasarell concluded the presentations describing Kramer as “a good man, a champion in life.”

During my 25-year career covering tennis for three daily newspapers, I always felt confident that I had strengthened my profiles, features or commentaries whenever Kramer’s insight was included. During several interviews with Kramer, I often wanted to mention to him how much he had influenced my love for the game as a junior player. Like many youngsters drawn to the game during the 1950s, I learned to play with a Jack Kramer endorsed wooden racket and at the time, it was my most precious possession.

In Baltimore, a couple hundred people assembled at the Rawlings Conservatory and Botanic Gardens – the site where the ATA held its first National Championships (1917) – to honor Baltimore’s African American tennis pioneers who played and promoted the game despite racial barriers before, during and after the Civil Rights Era. Ann Koger, Haverford College (Pa.) women’s coach for the last 29 years, was the event’s mistress of ceremonies and Robert C. (Bob) Davis, Director of Adult Programs for IMG, the sports firm that owns Nick Bollettieri’s Academies, was the keynote speaker.

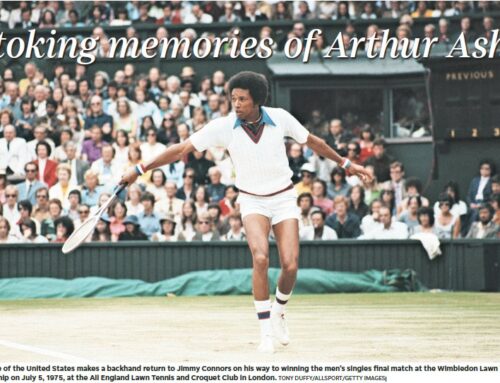

Davis, a lifelong friend of the late Arthur Ashe, was a top ATA junior in the 1950s and later, as a young adult in the 1960s. Founded in 1916 in Washington, D.C. by a group of African American businessmen, college professors and physicians, the ATA was the counterpart to the United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA), which barred minorities from its events during most of the 20th century. Among other impressive accomplishments , Davis also owned and managed a private tennis academy in upstate New York and was co-founder of the Arthur Ashe Safe Passage Foundation (1987-96).

Davis reflected on his early years in tennis and praised the late Dr. R. Walter (Whirlwind) Johnson, who was recently inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame, and the late Dr. Reginald Weir, the first male to win the ATA national title three consecutive years (1931-33). Davis mentioned that Baltimore’s two ATA tournaments – the Baltimore Tennis Club & the Netmen Coed Tennis Club – were among his favorite events. Davis closed his remarks with warm appreciation and gratitude to Baltimore’s pioneers who were cited during Saturday’s celebration.

“You saved my life,” Davis said. “And there are hundreds of thousands of other kids out there who also owe you a debt of gratitude.”

I, too, am among those who benefited from the efforts of Baltimore’s tennis pioneers: Joseph Boston, Leon Bowser, Nellie Briscoe Garner, Lelia Lucille F. Davage, Llewellyn Davage, Franklin Fitzgerald, Myrtle Koger, Joseph P. Parham, Sr., Jean Powell, Dr. Alfred Sutton, Warren W. Weaver, Irvington ‘Rip’ Williams and John ‘Junky’ Wood.

Leave A Comment