In the final segment of our Where Have All the Black Male Pros Gone, we’ll trace the history of the African American male’s entrance into the once segregated white world of tennis, review observations and insights offered by three prominent tennis coaches, recognize several other talented black juniors who became pros, and most importantly offer recommendations for the USA’s tennis powers-to-be to consider.

We begin with the early development of the late Arthur Ashe, who was dubbed by his contemporaries as ‘the Jackie Robinson of tennis.’ Arthur, a Richmond, Va. native, reached the highest level of the game thanks primarily to the generosity and persistence of one man: Dr. R. Walter (Whirlwind) Johnson, who formed the nation’s first junior development program on his backyard court In Lynchburg, Va. in the 1950s.

Whirlwind wasn’t just about putting Ashe on a path to tennis greatness. He had bigger dreams. As the headline on a 1969 Washington Post story suggested, Whirlwind aimed to “Change the Color of Tennis.” He was convinced that if given the training and guidance needed, a black player could become a great tennis champion despite the barriers of that time. Whirlwind told the Washington Post, “What made me maddest, though was this idea that colored athletes were only good as sprinters or strong boys, that they couldn’t learn stamina or finesse. And somewhere I’d read an article that said flat out there’d never be a great Negro tennis player.”

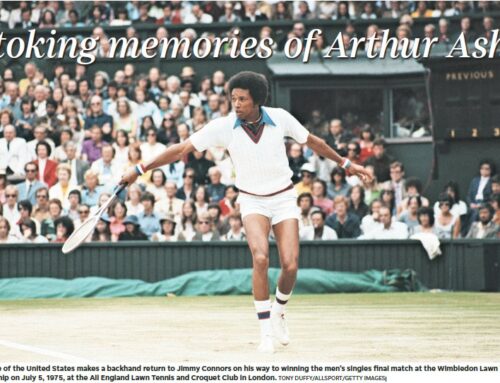

Whirlwind dispelled that notion in his role as the key developer of Althea Gibson and Ashe, the USA’s first, great African American tennis champions. Gibson, raised in Harlem (NY), was the first black woman to win a Grand Slam singles (French Open, 1956). The Florida A&M graduate also won the U.S. Open (1957-58) and Wimbledon (1957-58). Ashe, a UCLA graduate, captured the inaugural U.S. Open in 1968, Australian Open (1970) and Wimbledon (1975).

Ashe’s rise to fame came in the midst of the Civil Rights era and fueled interest in tennis in black communities. It also prompted Whirlwind to expand his search for other talented juniors. He didn’t have to travel far to find one of his best protégés, Juan Farrow, who lived next door.

Farrow was four years old when Whirlwind put a broom handle, instead of a racket, in his hands and taught him to hit balls with it. Whirlwind told him that if he could learn to hit a ball with a broom handle, he’d have no problem hitting a ball in the middle of the strings with a racket. During a 1980s interview with him for my book, Whirlwind, the Godfather of Black Tennis, Farrow said, “I guess the thing that he most instilled in me was to keep your cool at all times. I feel that has been a trademark of all the people who have ever been under his wings. Whether they made it or not, all have been cool on the court.”

Juan exceeded Whirlwind’s expectations by becoming the USA’s No. 1 ranked player in the 12-and-under division in 1971, the year Whirlwind died. Two years later, he was the top-ranked player in the boys 14-and-under division, posting victories against several future pros, including John McEnroe. “I beat McEnroe in 1977 about four weeks before he reached the Wimbledon semifinals. That also was the last time I played him.”

Lenward Simpson, Arthur Carrington, Chip Hooper, Horace Reid and Luis Glass were among scores of black juniors of the 1970s inspired by Ashe’s success. What happened to that cadre of talented black male juniors and what has kept most talented black pros since from capturing major titles during the last 45 years? Teaching pros Bob Davis, Rodney Harmon and Rozzell Lightfoot provided some answers in the first three installments of our Where Have All the black Pros Gone series, which were published on this website a few weeks ago.

Davis, one of Ashe’s teammates on Whirlwind’s junior development squad, cited finances as a reason why many black juniors cut short their pursuit of pro tennis careers. “It’s well-documented that families must spend $60,000 to $80,000 minimum per year for a player to achieve and maintain a national ranking,” says Davis, once affiliated with the Nick Bollettieri Tennis Academy.

Harmon, former director of the USTA men’s team, noted the reluctance of the United States Tennis Association (USTA ) to become ” more involved with identifying and assisting multicultural players. When I look at Rafa (Nadal), Andy (Murray), Roger (Federer)and Novak (Djokovic), I see excellent tennis players who also are gifted athletes, capable of performing at the highest level in a number of other sports. To compete against today’s top pros, we must find players who can match up athletically. If the USTA is serious about competing with the rest of the world, it must get serious about working with top multicultural programs, coaches and players. ”

Lightfoot, a former director of tennis at the Washington Tennis and Education Foundation (WTEF), said, “Experienced African American players and coaches are under-utilized. Every African American that has been successful at the highest level in the history of American tennis has always been coached or mentored by African Americans.”

Indeed, Willis Thomas, Jr. and John Wilkerson combined their coaching talents to guide Zina Garrison and Lori McNeil to top 10 status in the 1980s. Garrison was a Wimbledon finalist in 1990 and reached a career high No. 4 ranking in 1989. McNeil was a U.S. Open semifinalist in 1987, a Wimbledon semifinalist in 1994 and reached a career high No. 9 ranking in 1988. Thomas, who was Ashe’s doubles partner in the boys 12-and-under division, also coached Harmon during his junior years. Despite their success neither Thomas nor Wilkerson was pursued by the USTA to join its coaching staffs. Thomas contends that the absence of black coaches in the USTA junior development program is a key reason why the number of black men in pro tennis continues to tumble.

“I believe there are not any black players in the top 100 because there are not many black coaches on the USTA staff,” Thomas said. “The USTA gives most of the jobs to former players with little coaching experience instead of lifelong coaches that have proven they can take players to the next level. Black players generally play a style which their USTA coaches cannot understand. Because of a lack of understanding of these styles, they (USTA coaches) usually change the players strokes to conform to a style the coaches understand. This leads to a confused player with no confidence.”

Put simply, the elephant in the room that was raised by my guest columnists, is racial bias, the same pollutant that has plagued our shores since the country was formed. In today’s politics, we’ve seen how divisive it can be at every level of government and particularly since the White House is now occupied by a black man. Not surprisingly, the Tea Party-backed members of Congress chose to risk the stability of the nation rather than support Obamacare. The government shutdown reminded me of the pre-Civil Rights era of stories about ailing whites in the South who chose to die rather than receive potentially life-saving treatment from black physicians.

So we shouldn’t be shocked when signs of racial bias popup or become more evident in other areas of our society, especially in fields, such as tennis and golf, which are isolated from the mainstream by wealth and/or privilege. When I think of the odds against two African Americans – Tiger Woods and Serena Williams being proclaimed the greatest ever in their respective white-dominated sports, I smile inwardly and delight in the knowledge that our Deity does have a marvelous sense of humor.

Richard Williams showed us a way to circumvent racial barriers when he guided his gifted daughters, world No. 1 Serena and Venus, to greatness in tennis. When the sisters were youngsters, Williams said he observed the fanaticism of some tennis parents and knew it would be a mistake to subject his daughters to the USTA’s junior tournament circuit and its ranking system. Williams, then based in Compton, CA, took them to Rick Macci’s Tennis Academy in Florida, where they showed great promise and trained diligently but never played junior tournaments. One of the Williams’ family most-publicized encounters with racial bias occurred in March 2001 at an Indian Wells, CA. event where Serena – while facing Kim Cljsters in the final, was booed mercilessly throughout the match. Williams and Venus, sitting in the stands, also were booed. Williams vowed never to return to that event and his future Hall of Fame daughters have not played there since the incident.

Could Williams’ strategy be used to carve a pathway to success for the next great black male hope in tennis? My guest columnists – and the facts of tennis history – tell us that, right now, it might be the only path now available.

Gibson, Ashe, Venus and Serena Williams are still the only blacks to win Grand Slam singles events. All were developed and nurtured by coaches/parents who cared for them unconditionally and understood that mastering the game wasn’t the only lesson that they had to pass on.

Though there have been many black juniors ranked No. 1 in the world or in the USA (before world junior rankings) over the years none became top-ranked pros. Just last year, Taylor Townsend, a gifted lefthander from Boca Raton, FLA, became the first American girl to be ranked No. 1 in the world since 1982. Incredibly, the USTA attempted to deny the Australian Open Junior champion the opportunity to play in the 2012 U.S. Open juniors, refusing to pay her expenses despite her achievement. Patrick McEnroe, who heads the USTA’s Player Development Program, cited her “excess weight” as a reason for taking the action.

One wonders how far Martina Navratilova or Lindsay Davenport would have gotten if the USTA had denied either of them expense money due to excess weight. Some journalists and former pros described McEnroe’s action as insensitive, more harmful than helpful. It certainly was inappropriate. If the USTA truly wants Townsend to reach her potential, it should hire additional qualified coaches of color and give them the responsibility and support needed to work with all members of the junior development program. Coaches should be hired by their ability to produce elite pros, not by their philosophical approach to teaching tennis. If coaches can identify, develop and guide two players to top 10 pro careers as Wilkerson and Thomas did with Garrison and McNeil in the 1980s and 1990s, why not give them a chance to do the same for the USTA Junior Development Program? The logic of not pursuing that kind of success baffles me still.

What’s kept other black male pros from claiming major titles since Ashe captured the first 45 years ago? The same indifference and lack of commitment by some of the tennis powers-to-be that’s threatening to derail Taylor Townsend’s promising career before it gets started. If the USTA truly want black juniors to make the transition from top-ranked junior to top-ranked pro, it should make the necessary adjustments.

Like Whirlwind before him, Ashe, who died of AIDS complications in 1993, helped other blacks to become top players. He solicited college scholarships for dozens of promising juniors, gave money to many and sent others to tennis camps for advanced training. He also organized clinics for black coaches and met with several groups of black coaches periodically to discuss various player development programs.

When Stan Smith was named head of coaches of the first USTA junior development program in 1986, Ashe lobbied successfully for a black coach (Benny Sims) to be one of the four other USTA coaches selected for that program. Ashe was a mentor to Harmon, also a Richmond native, during Harmon’s playing and USTA coaching careers. Before Ashe died there were dozens of black pros and promising juniors on the various pro circuits. Their presence in the game, I’m sure, was another example of his success. And, of course, Arthur’s success – on and off the court – had much to do with the Ashe statue that looms above the promenade that leads into the Arthur Ashe stadium at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, site of the U.S. Open.

Since 1992, an Arthur Ashe Kid’s Day is held on the Saturday before the U.S. Open begins. It is a celebration of the memory of Ashe and of his efforts to help young people through tennis. The event has been well-attended each year, but as Howie Evans, the Amsterdam News sports columnist, noted a few years ago, more should be done to make attendees aware of Arthur’s life achievements. I concur. A connection to Ashe should be a part of the Arthur Ashe Kid’s Day celebration.

I believe, too, that the best way to recognize and honor Arthur’s efforts would be for the USTA to make a firm commitment to attract promising African American juniors to the game and to include African American coaches in the development process. When talent comes to surface in the form of Townsend or whomever, be helpful and supportive. Avoid even the slightest urge to prejudge, discourage or discriminate. And keep in mind how difficult the road might be for some travelers, as it was for Ashe himself. In his book Days of Grace, Arthur told a People magazine reporter, that having AIDS wasn’t the heaviest burden he’s had to bear. “You’re not going to believe this but being black is the greatest burden I’ve had to bear,” he wrote “….. My disease is the result of biological factors over which we, thus far, have had no control. Racism, however, is entirely made by people, and therefore it hurts and inconveniences infinitely more.”

Leave A Comment