When comparing crowd reactions to superstar Tiger Woods and Phil Mickelson last summer, a golf analyst offered this succinct observation: “They respect Tiger Woods but they love Phil Mickelson.â€

The same conclusion could be reached in comparing crowd reactions to tennis’ top-ranked Serena Williams and her sister, Venus, vs. any opponent. I’d like to believe that the reason for the clearly partial crowd support for the fairer complexioned player has more to do with racial preference than racial bias. But deep inside, I’ve come to understand that the former is merely a euphemism for the latter. Like golf, tennis is a pro sport that has had only a handful of outstanding African American champions to reach the elite level. All had major obstacles to overcome or troubling roadblocks to circumvent. Residue from that era of racial bigotry lingers still.

Indeed, the Williams sisters at times have been treated by fans, media and tennis officials like unwanted step-children rather than rare, national treasures.

Cases in points:

• I was near the USTA president’s box in Arthur Ashe Stadium when 17-year-old Serena Williams bolted onto the tennis stage by upsetting top-ranked Martina Hingis in the 1999 U.S. Open final. A major upset victory by a rising American star against a Swiss No. 1 should have evoked excitement in the nation’s tennis hierarchy, but no palpable sense of love, pride or joy flowed from most of those in the president’s box that day. Only polite applause.

• U.S. tennis fans generally love their superstars –even the bad ones (Jimmy Connors, John McEnroe), but demand disciplinary action when required. Rarely do they demonstrate any level of hostility toward any player based on suspicion. However, fans at the 2001 Indian Wells (CA) final proved to be the exception. They went far beyond the boundaries of decency, some even reveled in their cruelty. For two hours they booed intermittently the Williams family – Richard and daughter, Venus, in the stands and Serena, while facing Kim Clijsters in the final. The fans’ loathing of the Williamses, was prompted by media speculation that Venus lost intentionally (faking an injury) to Serena in the semifinals. The family denied the allegations and Serena, despite the disconcerting, at times hostile, home crowd, defeated Belgium’s Clijsters in the final. The sisters, who remained gracious and poised throughout the debacle, have refused to play Indian Wells since the incident.

• With an international television audience watching, U.S. Open officials allowed Jennifer Capriati to win a quarterfinal match against Serena even though they – and the watching world – knew that the chair umpire had made three blatantly bad calls against Serena in a close match. The crowd cheered when Capriati claimed her tainted victory. However, the incident led to the implementation of a players’ challenge system via instant replay. The unfairness of the moment brought back similar moments I’d experienced years ago watching talented black juniors robbed of victories against white juniors.

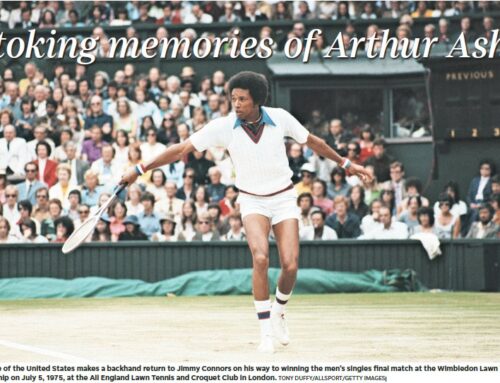

From the playing days of Althea Gibson (1950s), Arthur Ashe (60s and 70s), Zina Garrison and Lori McNeil (80s and 90s) to Serena and Venus Williams, black tennis champions –in their prime – have been admired and respected for their talent, but they’ve never captured the hearts of U.S. tennis fans, especially when facing white compatriots. Gibson and Ashe were trailblazers who rode the spiritual support of an oppressed people to overcome the odds despite the barriers. Garrison and McNeil, trained and nurtured early on by black coaches John Wilkerson and Willis Thomas, succeeded despite dishonest tactics by junior tournament officials that included placing all black juniors in the same quarter of draw to prevent more than one black junior from advancing to the quarterfinals. Sensing that the deck would be stacked against them, Richard Williams wisely kept his daughters out of USTA junior events, opting instead to allow them to enjoy their childhood before embarking full-time on pro careers.

The absence of passionate crowd support for African American players is but one indication that the powers-to-be in tennis aren’t eager to welcome or embrace a large contingent of black champions. There are many others:

For example, one promising black junior who trained at a prestigious Florida tennis academy told me years ago that he was used mainly as a “sparring partner†for top white juniors. “I never got the one-on-one attention that the white players received,†the black junior said. “I felt like a human backboard.†When asked about the lack of top black stars in tennis during a press conference in the ‘90s, a white journeyman pro said, “They have basketball and football. Tennis is our sport.â€

The late Gene Scott provided the tennis community another reason in a commentary he wrote in his publication, TennisWeek in 1999. He noted that there were no African Americans on the International Tennis Hall of Fame executive committee, no African Americans at the highest levels of the ATP and WTA tours, no African American tournament directors on either tour and only a few African Americans executives in other major tennis organizations, including the USTA, which had only one African American on its board of directors at the time.

Not much has changed in the tennis hierarchy since Scott, who was inducted posthumously into the Tennis Hall of Fame, died several years ago. A thoughtful man of integrity and a gifted writer, Scott worked arduously to make tennis the sport of a lifetime for everyone. He chastised me frequently for not doing more to help him expose what he perceived to be “greed and corruption†in high places in tennis. I still have documents provided by Scott, that include data about exorbitant salaries paid to top tennis executives. I believe the man and his publication are sorely missed by most members of the tennis community. Like many white Americans who value fairness and integrity, Scott didn’t make decisions about people based on their ethnicity.

Will tennis or golf ever attract more African American juniors with the potential to become great champions? Maybe, but that’s not likely. Why not? The reason represents the intangible barrier that still divides the races. In sports and in life in general, the nation’s racial woes have much to do with the inability or unwillingness of a large segment of white America to see, feel and care about what reality was, and to some degree, continues to be for us.

Leave A Comment