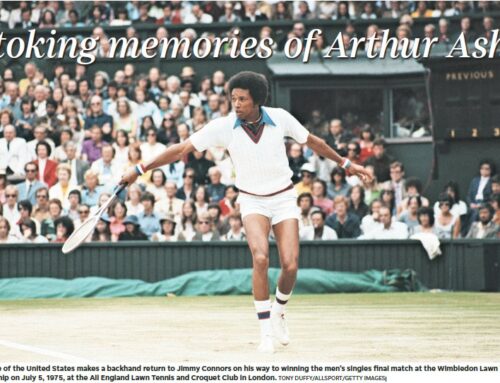

When the Open Era began in tennis more than 40 years ago, U.S. pros were the players-to-beat on the men’s and women’s tours. Arthur Ashe, Stan Smith, Billie Jean King, Jimmy Connors and Chris Evert were among the first wave of American champions nearly always in contention for tournament titles, including the majors – Australian Open, French Open, Wimbledon and U.S. Open.

But in recent years the number of U.S. contenders has dwindled to a precious few, and once the Williams sisters and Andy Roddick hang up their rackets, there’s a good chance no Americans will be among the top challengers on either tour, at least for awhile.

The Australian Open begins this week with only three Americans – defending champion and top ranked Serena Williams, her sister, No. 6 Venus, and No. 7 Roddick, – ranked in the top 10. Moreover, the country that once placed more than 50 players in the top 100 on the WTA and ATP tours annually now has only a dozen or so gaining direct entry into the season’s first Grand Slam event.

Significantly, No. 48 Melanie Oudin, 18, is the only rising star among the other three U.S. women in the top 100 and No. 34 John Isner, 24, is the youngest among the other eight U.S. male pros in the top 100. Other top 100 U.S. pros: (women) No. 76 Jil Craybas and No. 80 Vania King; (men) No. 25 Sam Querrey, No. 34 John Isner, No. 44 James Blake, No. 55 Mardy Fish, No. 76 Taylor Dent, No. 79 Rajeev Ram, No. 83 Michael Russell and No. 100 Robby Ginepri.

Several U.S. tennis officials and former pros insist that the absence of USA pros at the highest level is nothing more than a “cyclical reality.†They say other countries might dominate for awhile, like Sweden did in the 70s during Bjorn Borg’s reign, or Germany in the 80s during the Boris Becker-Steffi Graf era, before the USA rebounds, as it did in the 90s during the Pete Sampras-Andre Agassi glory years.

But the erosion of America’s presence at every level of the junior, college, and pro game suggests a more lasting and troubling problem. Consider the differences in the following areas:

· U.S. tennis academies – In recent years our nation’s academies, once a primary training ground designed to turn talented U.S. juniors into pros, have developed and turned more foreign juniors into top pros.

· U.S. colleges/univesities – Brad Gilbert, Todd Martin, Lisa Raymond and MaliVai Washington were among dozens of U.S. students who used college scholarships and superb coaching to make it to the pro level. In recent years our college scholarships at every level have gone to foreign student/athletes.

· Loss of tournaments played on U.S. soil – In the 70s, the U.S. hosted more than 30 men and women tour events. Since then, more than a dozen, including the tours’ season finales, which were held annually in New York’s Madison Square Garden, have moved to other countries. Ten years ago, the U.S. hosted 16 men’s events; last year it hosted only 10.

· Absence of athletically talented preteens drawn to tennis. – The nation’s best young athletes, especially from African American communities, migrate to basketball, football and baseball. U.S. juniors generally get introduced or learn the fundamentals on suburban or country club courts. Size matters as much as talent at the pro level. Today’s tennis pros are stronger and bigger than old school champions. The average height of players in the men’s top 10 is 6’2”; the average height of the top 10 women is 5’10”.

The absence of diversity at every level of tennis is also a serious impediment. Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe, the nation’s first great African American champions were unwanted tennis lovers with something to prove. No other person of color rose to No. 1 until the Williams sisters, Venus and Serena, and they succeeded without playing USTA junior events. I’ll have a bit more to say about that in a later blog.

To curb the decline of the U.S. as a tennis power, the United States Tennis Association (USTA) and related organizations must, among other things, focus more on building a more diverse and larger talent pool of juniors. To do that, it must become a bit more concerned about truly growing the game at the grass roots level. In recent years, USTA leaders seemed obsessed only with creating a money-making fantasy of the U.S. Open and nothing else. Recent personnel changes suggest they might have made a philosophical change for the better.

Leave A Comment