Before Arthur Ashe became Virginia’s No. 1 black junior tennis player, Henry Livas, Jr. was the states’ top black teen. During the era of racial segregation, Henry led Hampton’s Phenix High School to the black state championship in 1955-56, winning the singles and doubles (with Billy Neilson) titles.

Before Arthur Ashe became Virginia’s No. 1 black junior tennis player, Henry Livas, Jr. was the states’ top black teen. During the era of racial segregation, Henry led Hampton’s Phenix High School to the black state championship in 1955-56, winning the singles and doubles (with Billy Neilson) titles.

In 1955, Henry caught the eye of Dr. Robert Walter ‘Whirlwind’ Johnson at the American Tennis Association’s (ATA) National Championships by capturing the ATA’s junior doubles (with Billy Neilson) and mixed doubles (with Clara Henry) and singles finalist, losing to California’s Willis Fennell. That year, Johnson selected only three players – Henry, Fennell and Beverly Coleman, another Californian, to his newly formed junior development team. The players spent the summer at Johnson’s Lynchburg home where they practiced and trained on the clay court he built in his backyard. For more than 20 years, Johnson, a black physician, trained more than a hundred black juniors on his backyard court to prepare them to play in United States Lawn Tennis Association (USLTA) tournaments throughout the country. Johnson was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame as a contributor in 2009.

Henry also was a starter on Phenix’s varsity basketball team and competed in both sports with admirable toughness and tenacity. He needed much more against Fennell, who played a strong West Coast serve-and-volley game. Fennell beat Henry routinely in straight sets. Before the summer ended, Henry had enough. “I just got tired of losing to Fennell every week,” he said. “So, I packed my bags and went home. Doc wasn’t too pissed off at me. I think he understood.” The day after Henry left, Johnson called Richmond to let 14-year-old Ashe’s father know that his son’s Lynchburg summer room was ready.

Henry and I really didn’t spend that much time together during our 61-year friendship. We recognized that in our formative years we had the pleasure and privilege of competing against Ashe, a childhood friend, who became one of the game’s all-time greats and a global icon. We were a part of the ATA family and our love of tennis was our primary bond.

We first met on Hampton University’s tennis courts in the early 1960s, when I was a member of Hampton’s varsity tennis team. Henry grew up on Hampton’s campus, where his father was an architecture professor. Then a Bucknell University team member, he was home for the summer. We chatted during my practice breaks. I knew he had beaten Ashe several times in ATA junior events; he knew that Ashe, Maggie Walker High’s No. 1 player (1959-60), was 5 and 0 against me when I was Phenix’s No. 1. I sensed that Henry had something on his mind and wanted to pass it on to me and my teammates. With his infectious smile in full bloom, he said, “You know, Doug, I’m the only black player who has a winning record (5-2) against Ashe.” Interesting, I thought, but I said nothing.

My teammate Sid Moore, however, verbalized his thoughts with a devilish grin. “Hell, Henry, you were a teenager (16) and Ashe was just a kid (11) when you beat him,” Moore said. “Sounds more like child abuse to me.” Over the years Henry used his I-beat-Ashe story as an ice-breaker many times. If you’re a tennis player/fan, it will get your attention.

My teammate Sid Moore, however, verbalized his thoughts with a devilish grin. “Hell, Henry, you were a teenager (16) and Ashe was just a kid (11) when you beat him,” Moore said. “Sounds more like child abuse to me.” Over the years Henry used his I-beat-Ashe story as an ice-breaker many times. If you’re a tennis player/fan, it will get your attention.

Henry got my attention routinely at the U.S. Open Tennis Championships during the 15 years I covered tennis for USA Today. When he retired from NASA Langley Space Center, where he worked as civil engineer, we got together several times in London when I covered Wimbledon. I believe we met in Paris once at the French Open, and I know he had wanted to get to Melbourne for the Australian Open, so that he could say he had seen, in person, professional tennis played at the four major events.

Wherever we were, we chatted mainly about the top pros, and of course, we also reminisced about our early years with the ATA. While having lunch at Wimbledon, he flashed a smile and said, “You know, Doug, I’m the only black …”

“I know, Henry, I know,” I said, before he could finish.

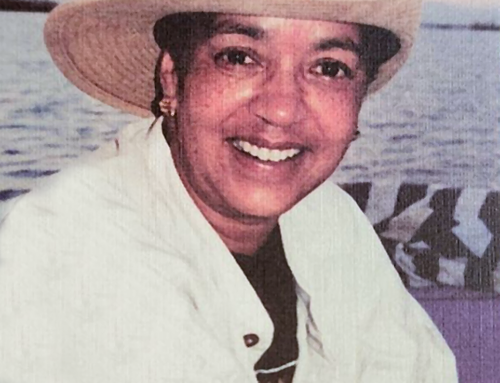

Henry Livas, Jr., 82, was buried February 25, 2021, in his hometown, at the Hampton Memorial Gardens cemetery. He was survived by two daughters, Cosette and Nicole and two sons, Leonard and Nicholas.

I want to thank Doug Smith for his thoughtful tribute to the late Henry Livas. Henry was a trailblazer as a Black civil engineer. He served as an inspiration for my professional career. Condolences to his family. May he rest in peace. From Knox Tull of Hampton, VA.